All sorts of interesting people come through the doors here at Stage One. Most often, however, they speed past our small marketing team and straight into a meeting with a project manager. Or alternatively, head straight down the office with said PM and out to the workshops to see first-hand how their project is progressing. As one third of marketing, my job is generally confined to writing about our projects. Chatting to visitors, however fascinating I think they may be, is just not part of my role.

A podcast, though. What a great opportunity to find out more about the interesting people we see fleetingly before they’re squirrelled away into meeting rooms. What a great opportunity to be nosy! A chance to chat, at length (thanks to editing) and with no interruptions. We didn’t let limited equipment and a complete lack of experience put us off. We started with artists.

Why Artists? Stage One work with all kinds of creative people yet our work with artists is particularly varied. Also, as creative manufacturers, talking to those at the perceived pinnacle of creativity had a certain logic. We also had an inkling that they might surprise us.

The artists we work with at Stage One thrive on collaboration. That’s usually why they’ve come to us. We’ve worked with creative ideas at all stages of development: from a basic felt pen sketch to a fully detailed design complete with samples and a whole catalogue of references. For us, the process is a rewarding one regardless of where we come in because the collaborative relationship is usually quite a personal one, yet the resulting artworks are incredibly varied and experienced by the many.

Don’t be deceived by the need for collaboration: artists are also deeply practical people. They’re used to solving practical problems or finding new routes (or people like us) who can help realise their conceptual works. They’re knowledgeable about materials, methods and the means to realising their works but are also incredibly receptive to new ideas. They look to collaboration to push the boundaries. To innovate.

The intertwined threads of practicality, innovation and a thirst for knowledge appeared throughout all our podcast conversations. They challenged our natural tendency to try and categorise people by discipline or their means of earning a living. An artist is, well, not just an artist.

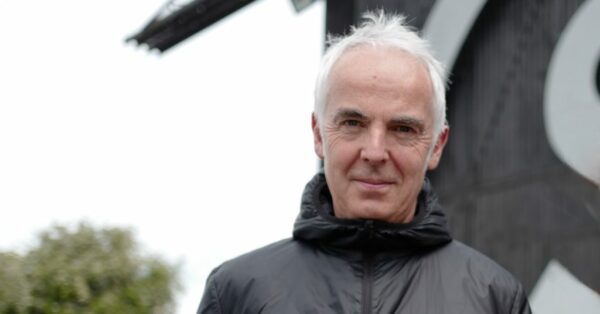

Jo Fairfax’s work embodies his natural enthusiasm, engineering creativity and inventiveness. He started young and revealed how, aged ten, not wanting to get out of bed was a powerful motivator (though I’d argue its power at any age). Living in a freezing cold house with no central heating, he used a powdered milk can, pulleys and string to create a contraption that opened his curtains without having to get out from under the covers. Practical, imaginative problem solving at its stay-in-bed best. This spirit manifests itself in the processes and work of all the artists we spoke to.

Asked how artists and engineers differ, Jo went on to talk about his determination and defiance in the face of categorisation:

“I don’t like the idea of suggesting difference or boundaries of identity at all…I heard a radio programme that said the DNA of a person can be triggered at different times of life…there are parts of our personality, parts of our capabilities which simply lay dormant.”

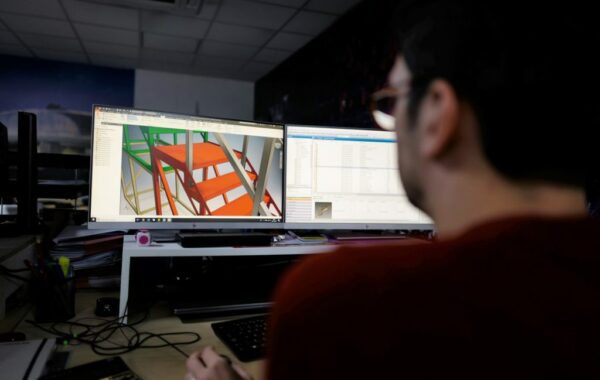

He is adamant that each one of us maintains massive potential, across all disciplines and for the whole of our lives. Reassuring, if slightly daunting, to hear. Curtain opening aside, practicality and a willingness to keep on learning were in evidence at a range of scales: from multi-disciplinary designer and sculptor Paul Bonomini describing how he’s recently learned to cast in bronze, to John Everiss finding a workable solution to welding thousands of 10mm washers into his ethereal half-there D-Day figures. Michael Eden’s toolbox, meanwhile, has shifted from the potter’s wheel to the virtual world: these days, computer code not clay is his medium of choice and it allows him to fashion intricate, highly detailed sculptural pieces while pushing 3D printers to their limits.

Back to labels and the struggle to resist categorisation. Michael Eden calls himself a ‘maker’, as opposed to an artist:

“There’s a perception that if you’re involved with new technology, with 3D printing in particular, then it’s a very hands-off process…and I question that. For me making isn’t just about the physical engagement with materials, its about understanding the processes and materials but its very much about ideas and about translating ideas into finished objects.”

We were also lucky enough to chat to Tom Higham, York Mediale’s Creative Director who shed light on the drive, collaboration and dogged legwork that gets these artworks into our public spaces. He also talked about DIY culture and how York Mediale wants to encourage people to create, rather than consume. To grant us all permission to try new things. Perhaps become artists ourselves… or engineers… or makers.

Children or rather a child-like curiosity was another common thread in all five conversations. When we asked our guests about watching people reacting to and interacting with their work, everyone mentioned children. It seems they are the perfect barometer dispensing spontaneous reactions, natural curiosity, unselfconscious joy and of course, brutal honesty. Us adults are way too worried and weighed down by what we think we should think when we experience art. Perhaps next time I go to a gallery or visit an arts festival, I’ll take a small child with me and do what they do. Try and see what they see.

Podcasts were a new idea for us. Rookie mistakes aside, (put a sign on the door when recording, don’t print your notes on both sides of the paper and don’t be too quick to stop recording either) we found it fascinating, fun and hugely informative to delve a little deeper into the day to day working lives and inspirations of artists and designers. For us, being nosey paid off nicely.

If you’d like a listen, you can find all five episodes of Behind the Design, plus audio extras, over on Buzzsprout, Spotify and iTunes.