In 1969, Flight Director Gene Kranz was running the control room for the very first moon landing. He was conducting the most audacious project ever undertaken. He was the man in charge and so when he barked ‘keep the chatter down in this room’ that’s exactly what people did. They were 102 hours into the flight of Apollo 11 and the next few minutes were to be about as critical as anything ever gets.

And whilst it’s a lofty analogy, I’m reminded of this each time we’re about to deliver a show. This week we delivered the staging, flying system and stage engineering for the UAE’s 48th National Day at the Zayed Stadium in Abu Dhabi. This was a spectacular show that had been six months in planning. It also happened to be our biggest project of 2019.

I was in the control room and the next forty minutes would ultimately determine the success or failure of the entire undertaking. Despite the ubiquitous air con I was definitely sitting in the hot seat.

Comms is everything. The show caller taking the role of Gene Kranz, making sure everyone knows exactly what is to be done when. At showtime, the show caller is king or queen of everything they survey. People do exactly as they ask. Without question. Without hesitation.

Of course, show blocking, technical rehearsals, dress rehearsals, cue to cues had all been taking place for weeks. The shape of the show becomes second nature. Some cues were cut, others adapted. But the flow of the performance was set.

Everyone knew what to do. The only thing left was to deliver the performance.

And then, instead of ‘keep the chatter down’ came the line ‘good luck everybody’. I hate the idea of being reliant on luck a minute before a show opens. ‘It’s not about luck’ is always my thought. It’s a visceral reaction to a well-meant comment. However, in a live environment where you only get once chance to get it right, a little luck rarely does any harm.

Just two days earlier we’d had a failure on one of our switches in the roof of the stadium. This had meant that after flying the moons up to position during the penultimate dress rehearsal, we had lost control of the flying system and had to limp through the rest of the session like a recalcitrant teenager. Like embarrassed parents we needed to understand what was prompting this behaviour.

It turned out to be a fibre optic network switch that had failed in the roof. In a frantic and fairly tense hour our riggers and technicians swapped it out and we were good to go again in time for the final dress rehearsal. Until this point, the very same switch had been working perfectly forever. So perhaps luck does have something to do with it. Network redundancy helps in most instances, but not always.

‘Standby everybody’. Ten, nine, eight, seven. You know the rest. Six months of planning distilled into six more seconds of waiting.

And so the show begins and people start breathing again. The waiting is the worst part. Standing by to standby. Once the show has started it has a momentum all of its own.

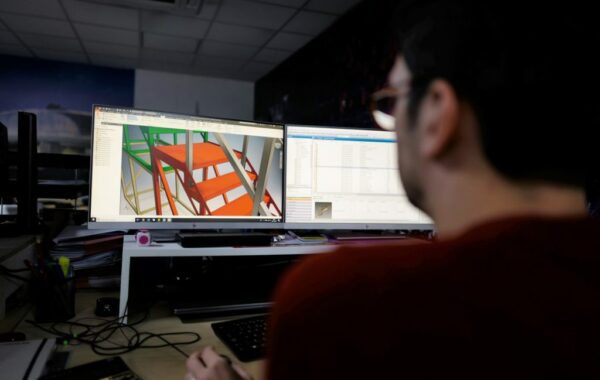

The control room was the hub for the aerial system and every element of stage engineering. A giant 50m diameter revolve, ten hydraulic scissor lifts and twelve winch farms that controlled the lifting and traversing of the scenic moons that flew around the stadium. We shared the space with a Belgian company responsible for moving twenty-four giant LED screens that rotated about their long axis on highly geared slew rings. Everything that moved in this giant spectacular was controlled from the desks in front of me.

Cues are called by the show caller. ‘Standby aerial, cue 7.42’. ‘Standing by’ comes the response from the operator as the cue is armed. ‘Go cue 7.42’ comes a few seconds later. ‘Moving’ is the simple but clear response from the operator as everyone starts to see the moons move into their ellipse position.

But the show caller is not just calling cues for automation. She’s calling cues for music, for performers, for plumes of water shot high into the air, for lights, for billowing flags, for confetti cannon and for marching soldiers who process purposefully to the protocol stage.

This is air traffic control. For performances.

And all the while I’m watching the cues count down through our Qmotion interface. The further down the list of cues, the closer we are to delivering a perfect show.

There’s an almost imperceptible delay between the operator calling ‘moving’ and seeing the hardware ramp up to speed on stage. It’s the briefest of moments, but always long enough to introduce doubt along the lines of ‘is it working?’. Seeing movement, or at least hearing the release of brakes is always very welcome.

It is relentless. There’s always a moment when it seems to be going according to plan that invokes a glimmering sense of hope. But it’s unwise to relax for fear of hexing the next cue or the one after that. Better to deal with things one at a time. Count them down. The control room is no place for counting chickens.

I’m always struck by the efficiency of speech. No padding. No flannel. No delay. Clipped tones. Stand by. Go. Moving. More than a hundred people linked by radio, executing cues right on time.

There were cues in this show that were fired by timecode. So exacting in their nature that they had to be coordinated precisely with other elements in the show without being ‘called’. Our Qmotion software deals with this brilliantly, and we used Kissbox hardware to deliver DMX signals via ethernet.

Using timecode is great. But whenever there is analogue input in the form of performers, other operators, or even a royal procession, there will always be a place for the show caller. And thank goodness, for they are a calming influence in the control room.

So almost forty minutes from the ‘good luck everyone’ call, the final cues are played out. The moons return to their pit. The show caller will whoop congratulations and the channels fall silent. Headsets removed. The show is over. The audience slowly files out of the seating block.

There is a moment, soon afterwards, that is hard to define. It’s not relief, nor contentment. It’s almost a hollow ‘what now?’ question that lingers for a few hours. But the job is done. And the control room goes home. Or more usually, for a drink.

And I suspect that’s where Gene Kranz went too.