Temporary structures, pavilions, dramatic centrepieces. Pretty much a regular day’s work at Stage One. It’s what we do: Exciting ideas brought to life through practical endeavour, resulting in enduring, memorable experiences.

Which is probably why this article on The Skylon caught our eye. The thin, elegant cigar-shaped design is iconic: distinctive, memorable, futuristic yet utterly of its time. It captured the post-war zeitgeist to a T and despite only standing for five months, the design and its memory have endured.

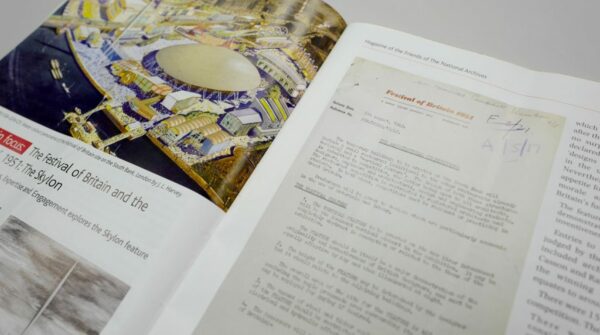

The article, in Magna Magazine, features the original Architectural Competition press release, calling for a ‘vertical feature’ to grace London’s Southbank for 1951’s Festival of Britain. Admittedly ‘Magna’ is a bit of a niche publication (it’s the magazine of the Friends of The National Archives) but in the header illustration, the Skylon stands magnificently and other-worldly on the banks of the Thames, a beacon of design and engineering, looking firmly to the future.

As a showcase for British innovation, in particular science, engineering and technology, the Festival called for structures that reflected this theme. To achieve this, they set up two architectural competitions for two temporary structures on the Festival site on London’s Southbank: the Dome of Discovery and a ‘vertical feature’. The press release for the ‘vertical feature’ is dated August 5th 1949, the modest, Courier typewriter font setting out a general spec and a few competition criteria. It’s familiar stuff: Expectation management. Budget constraints. Site constraints. An immovable deadline.

“The feature should in itself be a major demonstration of the originality and inventiveness of British designers, and must be equally effective by day and when illuminated at night.”

Drawing more from the limitations of austerity as opposed to obligations to sustainability, economy was a prime consideration:

“The amount of steel and timber employed in the construction of the feature should be restricted to a minimum but mechanical, electrical and hydraulic effects are not excluded.” and “Preference will be given to designs which are particularly economic in the use of materials and labour.”

The structure itself was manufactured in Hereford by Painter Brothers. A narrow latticework steel frame, standing almost 90 metres tall, tapered to a point at either end. The base was supported by steel cables slung between 15m high steel beams, giving The Skylon the appearance of floating above the ground. The joke at the time was that the structure had no visible means of support, just like the 1951 British economy… The frame was clad in aluminium louvres that reflected the sunlight and whistled as the wind blew through them. At night, it was lit from within.

But back to the competition that gave rise to that enduring and iconic design.

There were, in fact, 157 entries for the competition. These were judged by the Presentation Panel which included Festival of Britain Director of Architecture, Hugh Casson; Misha Black, a leader in the field of exhibition design; and designer of the Dome of Discovery, Ralph Tubbs. Interestingly, the assessors expressed some disappointment with the scope of some designs:

“Although a feature could take the form of a normal three-dimensional structure, it might well be composed of such non-structural elements as, for example, water, steam, gas or a combination of any of these. It is a matter of some regret that so very few competitors made use of non-structural elements.”

Yet despite regrets, they chose well. The winning entry, Skylon, was designed by architects Hildago Moya and Philip Powell. Structural Engineer, Felix Samuely ensured the design’s feasibility. It’s interesting to note that Moya and Powell kind of, almost, address the Presentation Panel’s ‘regret’. One idea they mooted was for a giant helium gas balloon but, as Powell reflected:

“There wasn’t enough helium in the world to fill it, and it would have cost £10 million if there had been.”

Unfeasible ideas aside, Skylon endures, in part possibly due to its fleeting, temporary nature. Yet there have been a few proposals to recreate it.

In 2004, The Guardian reported a proposal supported by the Royal Academy. Its president Phillip King was quoted as saying “You would see it in the distance like a rocket against the circle of the wheel. It is an extraordinary and still very powerful image. I hope it comes off.”

It didn’t.

The Academy asked architect Ian Ritchie to investigate the proposal: “Everyone I have spoken to has extraordinary sentiments about the Skylon. It was a very, very good design. I find it exciting. It was the godfather of the London Eye and the other tensile steel structures which now stand along the Thames.”

The Guardian revisited Skylon again in 2008. In his article “Skylon: is there a point in rebuilding it?” Jonathan Glancey notes how “Images of this ethereal, beautiful and endearingly fascinating Supersonic-era sculpture have haunted architects, artists, designers and engineers over the past six decades.”

If good design perpetuates and ripples in such a way, do we need to rebuild or recreate it?

A Skyscraper News interview with Hayden Nutall of Atkins (WS), leaders of the engineering side of the rebuild proposals, asked about Skylon’s enduring nature compared to other iconic yet now demolished structures. Nutall replied:

“It was so ahead of its time, there had never been anything like Skylon possibly anywhere, certainly not in the U.K. It was very, very beautiful…it seemed to defy gravity. People couldn’t work out how it stood up and most people thought perhaps it shouldn’t and was a magic trick but in fact it was just a great illusion pulled off with maths and physics.”

A great illusion pulled off with maths and physics? How very Stage One.

We’ll leave the last word to Professor Phillip King who said that Skylon “rang out like a challenge.” It may no longer be there, but the challenges Skylon represented are alive and well. And who doesn’t love a challenge?